Last week (June 13-15, 2018) there was an international seminar in Guatemala titled De la oscuridad a la luz, to celebrate the inauguration of a new section in the museum MUNAE: vitrines with original fragments of the famous San Bartolo murals. A great accomplishment! In this blog I want to make some comments on Dave Stuart’s presentation during the seminar called “Maya Creation in four Acts: A Study of Narrative Structure in the San Bartolo Murals”.

Stuart’s idea in itself is interesting, and is based on the two dates that have been found: 3 Ik’ which is on the West Wall and a fragment with the glyph 1 Ajaw, without context, found among the rubble of the other walls. He suggested that they formed part of an original series of four dates which guided the ‘reading’ of the murals. It recalls the birth of the people from Chicomoztoc depicted in the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, which indeed follows a calendrical sequence, an example, however, that was not mentioned by Stuart.

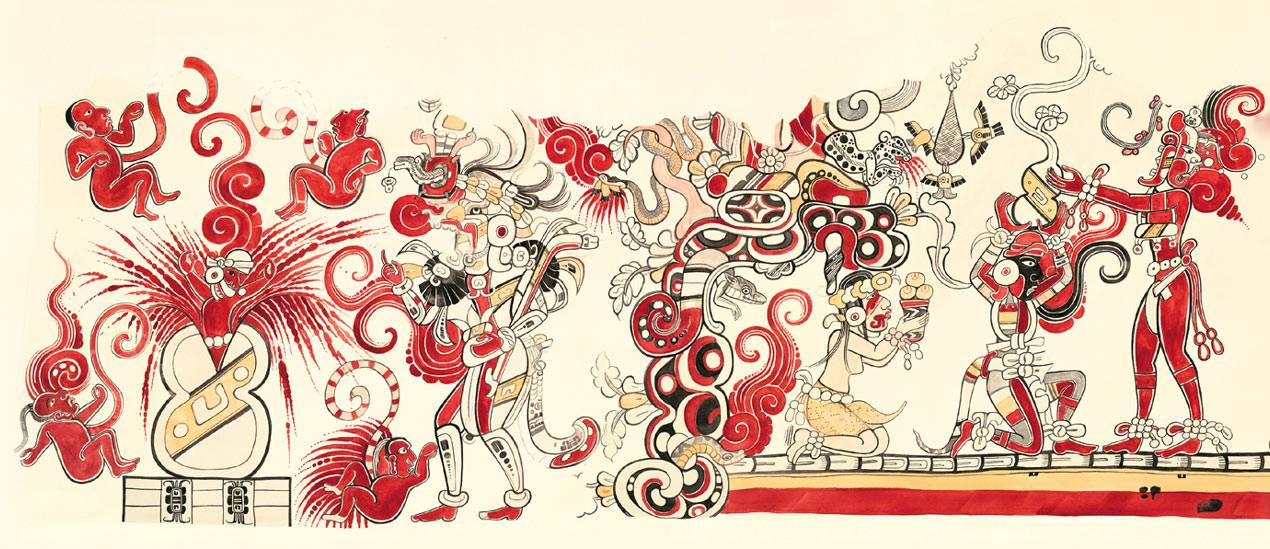

In his endeavor to reconstruct the San Bartolo narrative, he divides the murals into four scenes, two of which are on the existing murals and two imaginary others who belonged to the destroyed murals. In this effort he cuts off the Burst Tecomate on the North Wall from the Cave scene next to it, this way leaving the North Wall mural broken up. To him the Burst Tecomate scene belonged to the Throne scene on the West Wall mural. Why, he didn’t say; he just thought there was the cut in the narrative. There are various reasons against this cutting up of the North Wall.

First, of course, it is hard to believe that the creators of these murals did not know how to design their work well.

Second, the North Mural expresses an organic and thematic whole as I explained in my article Tzuywa: Place of the Gourd published in Ancient America (2006 – available online). Stuart and Taube keep saying the Exploding Tecomate or Gourd is an enigmatic scene, whereas I present a perfectly comprehensive exegesis for it in the article.

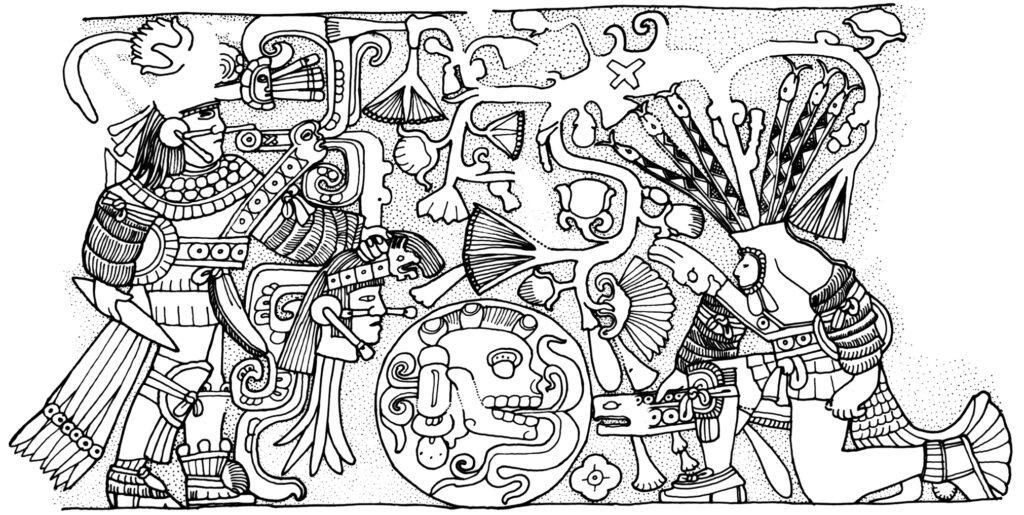

The Burst Tecomate is directly connected to the other, flowering tecomate on top of the kneeling person in front of the cave. As we know, Stuart and Taube claim that the scene represents a coming out of the cave, comparing it to various Chicomoztoc birth-scenes. However, the direction of the bodies, the feet, the faces and the footprints underneath – decisive indications in Mesoamerican iconography – suggest the protagonists are not moving out of but towards the cave. That has been my point: the cave represents the Maya Underworld and the ballcourt. The sacrifice accompanying the ballgame was the decapitation. The kneeling person is a ballplayer that is going to be beheaded, comparable to the scenes on Chich’en’s Itza great ballcourt benches. There, too, we have the flowering gourd symbolism.

In the Popol Wuj, the counterfeited head of Jun Ajpuuh is a chilacayote. In a beautiful play of words, we learn that from the burst chilacayote spring forth the Sons of the Sunrise (Saqil Al Saqil K’ajol), the first people made of corn. I have shown that in Mesoamerican mythology this fruit can be a gourd, a squash or a calabash, but one of the oldest forms must have been the tecomate (tzuh in ch’olano), as we see in San Bartolo. The Exploding Tecomate represents the Place of Origin known as Tzuwa, Tzuywa o Suyua in the indigenous documents, a place often coupled with Tullan and Seven Caves. The manikins leaping out of the fruit are the first people made of corn. Disconnecting this scene from the cave with Maize Hero and the kneeling ballplayer destroys the ancient cosmology intended by the painters.

That is just one reason for why it is unwise to separate the Burst Tecomate scene from the rest of the North Wall. There is another, an argument I didn’t see back then when I wrote Tzuywa: Place of the Gourd, but which I recently have explained in several conferences. It will appear in my soon to be published ethnohistorical study on Kaminal Juyu. We all know that the Maya believed that at the beginning of time three stones were created, the three hearth-stones or tenamastes, which were and still are part of many Maya households. From hieroglyphic texts we know these stones were considered thrones. Indeed, when in the Popol Wuj the Hero Twins arrive at the sacred hearth of Xibalba, its lords invite them to sit on the stones and the Twins answer that these are not their thrones. It turns out that the North Wall mural evokes these three throne-stones of creation – two of them are being carried by the black youths, who are heading towards the central ballgame scene, and the third is underneath the Burst Tecomate.

Kaminal Juyu was a Highland Maya site contemporary to San Bartolo. I propose in the new book that what we see painted in San Bartolo, we have in the real in Kaminal Juyu. Here we lack the space to expand on this subject, but it proves that the primordial throne-stones have a historical and geographical counterpart in the three volcanoes of the Valley of Antigua which still are known by their Poq’om-Maya names: Agua or Jun Ajpuuh, Acatenango or Pan Aj and the Fuego or Chi Q’aaq’, the name of the sacred oven itself.

Thus there is plenty of evidence that the Burst Tecomate forms an intrinsic part of the North Wall mural. Cutting it up would be a discourtesy to the artists who were expressing a millennial Maya cosmology which has been preserved from the Preclassic all the way to the times of the creation of the Popol Wuj, and even until modern times.